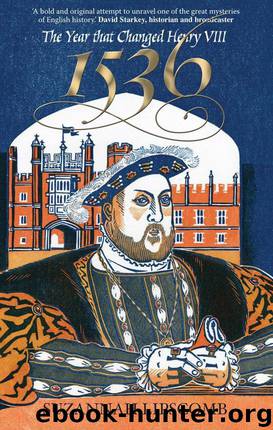

1536: The Year that Changed Henry VIII by Lipscomb Suzannah

Author:Lipscomb, Suzannah [Lipscomb, Suzannah]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Lion Hudson

Published: 2009-03-20T00:00:00+00:00

CHAPTER 13

Henry VIII’s Theology

Henry VIII’s theology seems to have situated itself somewhere between the later identities of Protestant and Catholic, and even somewhere between the contemporary beliefs of evangelicals and conservatives.

There appear to have been six key characteristics of Henry VIII’s theology, which were all present in the statements of doctrine produced in 1536. This is not to suggest nothing changed in Henry’s thinking – as we’ve clearly seen, his reaction to the rebellion of 1536 significantly altered his approach to monasticism, while his thinking on access to the vernacular scriptures fluctuated in response to the priority he gave to knowledge or unity. The people around him mattered too. Henry did not make policy in isolation and was in fact always quick to highlight the role played by his bishops and nobility in the creation of religious statutes and proclamations. Yet key values and themes emerge which do appear to be roughly consistent.1

The first was that for Henry VIII, the royal supremacy and his divine-right kingship under God, with responsibility for the cure of souls and the righting of religious abuses in the church, had become an article of faith. Henry had grown convinced of his unique position as God’s anointed deputy on earth, believing that the Supreme Headship was his birthright, and expected others to believe it too. This was contrasted in his mind with excessive clerical power and status. This was evident in the message clergy were told to preach in 1536, the king’s promulgation of doctrine, the stunning visual depiction of the supremacy on the title-page of the Great Bible and even in his questioning of John Lambert. His self-identification with leaders of the Old Testament, such as Abraham and David, is seen in such acts as his commissioning of the vastly expensive Abraham tapestries in 1540 to hang in his Great Hall at Hampton Court. It is also seen in the representation of David on the frontispiece of the Great Bible (suggesting Henry had picked up where David left off) and his approval of his depiction as David in the illustrations of his personal psalter which was presented to him in 1542 by Jean Mallard. Henry, like Abraham and David, was a leader who had a close relationship with God, modelled theocratic kingship and had a mandate to lead his people out of error into truth. In return for his royal care, he expected obedience from his subjects, in conscience as well as action.2

Secondly, Henry was preoccupied with preserving unity and concord in his kingdom. The Ten Articles had been entitled ‘articles devised… to establish Christian quietness and unity… and to avoid contentious opinions’, and the Six Articles and King’s Book reiterated this theme. So did an English primer, or prayer book, that Henry VIII issued in 1545. Designed to set forward one uniform manner of praying ‘for the avoiding of strife and contention’, it included a five-page-long prayer for the peace of the church, which vividly expresses Henry VIII’s horror of the ‘chaos’ of ‘evil wavering opinions’.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| General | Channel Islands |

| England | Northern Ireland |

| Scotland | Wales |

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(4155)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4143)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(3892)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(3680)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(3569)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3491)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3302)

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe(3107)

I'll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson(2871)

Shadow of Night by Deborah Harkness(2787)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(2768)

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography by Thatcher Margaret(2710)

Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Murder of Lord Darnley by Alison Weir(2700)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(2679)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(2635)

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum(2496)

Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell(2432)

The One Memory of Flora Banks by Emily Barr(2381)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2309)